According to the World Bank, “Financial inclusion means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs – transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance – delivered in a responsible and sustainable way.”

Written by Sofie Blakstad

Today, around 1.7 billion adults don’t have access to a bank account, for a variety of reasons: lack of funds, poverty and physical access issues being the main barriers. People without bank accounts can’t demonstrate credit history, lack insurance and face challenges saving, making them more vulnerable to economic shocks such as illnesses or business failures, suffering worse health, less likely to enrol children in education and more likely to suffer exploitation, particularly from middle men setting prices and local lenders charging extortionate interest rates.

Financial inclusion is a gender issue too

Amongst the people who lack access to financial services, there are also an estimated 350 million micro-businesses – from primary producers and retailers selling a small surplus from domestic produce to larger enterprises managed by family or community groups. And of the unbanked, there’s a consistent gender divide between men and women, with women being 9% more likely to lack access to financial services in developing economies. This exacerbates other cultural and legal inequalities suffered by women in many cultures, as they’re excluded from economic decisions. This, despite the fact that women entrepreneurs are known to make better decisions for their families’ long-term well-being, such as ensuring children are in school.

It’s not just a developing economy problem

Access to financial services is a persistent problem for lower income people and businesses all over the world. In the USA there are still 8.4 million unbanked households, with some urban populations such as Miami bucking the general downward trend as their unbanked populations increased in 2018, reflecting growing inequality. There are also very large numbers of individuals and businesses globally who are underbanked, i.e. those that have access to financial services but lack access to credit cards, affordable credit and other important services. Like the unbanked, this leaves them vulnerable to high interest rates charged by informal or alternative lenders. Many of the smallest businesses can’t access credit, restricting their ability to grow; despite small and micro businesses making up over half of the world’s economy, and being responsible for over half of global employment, the amount invested in, or lent to them, is around 2% of that invested in and lent to large businesses.

Great progress has been made

Since 2011, an estimated 1.2 billion adults have gained access to a bank account globally, reducing the global percentage of unbanked population by 20% in less than a decade. Fintech has played an important role in progressing this inclusion, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where the rise of mobile money has impacted both the absolute number of people with access to financial services and the gender divide – in countries with wide mobile money usage, women are disproportionately more likely to be mobile money users, giving them greater power of economic decision making and the ability to manage their businesses more effectively.

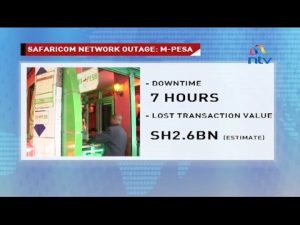

In Kenya, the birthplace of mobile money, M-Pesa moved the needle on financial inclusion from 17% in 2007, to nearly 100% of the population having access to financial services by 2017, while the number of people with bank accounts rocketed to over 60% in this time. Mobile money has been so effective because the mobile phone is such a critical tool in countries where there’s limited access to wifi, few desktop computers, logistical challenges caused by poor infrastructure and large distances and low incomes. More people in developing economies have access to a phone than to clean water, electricity or banking, and the price point of mobile phones makes them affordable even for the poorest.

Microfinance institutions were initially set up to address the issue of lending to unbanked micro-businesses, and have been successful in giving micro-businesses access to more capital, with an estimated 600 million micro-loans out at any one time. M-Pesa and other mobile money services are also moving into the microfinance space, with lending and savings products. Many governments have progressed financial inclusion through policy moves.

But there’s more to do

Mobile money services and digitisation of financial services have been transformational in Africa, but they don’t solve the whole problem; they are relatively expensive to use and Microfinance Institutions are expensive to run because of the high risk and administration cost of lending to this sector, while many charge very high interest rates; government caps on interest rates haven’t helped that much, as it’s causing lenders to restrict access to lending in response, although other government policies have been more effective.

Many of the challenges are barriers caused by factors they can’t directly control: physical access to bank branches, the challenges of identifying people with no credit history or formal ID, the risk and cost of moving money around. We can now add to that list, centralised services – bank and mobile money apps require connectivity to transfer money. Fintech solutions have been transformational and there’s now the opportunity to move to the next generation with blockchain and network analysis supporting movement of money and alternative identity for unbanked people and businesses. Our distributed, microservices system is being built to operate without permanent connectivity, helping communities save, transact and lend without the need for access to a central server.

Many of the challenges are barriers caused by factors they can’t directly control: physical access to bank branches, the challenges of identifying people with no credit history or formal ID, the risk and cost of moving money around. We can now add to that list, centralised services – bank and mobile money apps require connectivity to transfer money. Fintech solutions have been transformational and there’s now the opportunity to move to the next generation with blockchain and network analysis supporting movement of money and alternative identity for unbanked people and businesses. Our distributed, microservices system is being built to operate without permanent connectivity, helping communities save, transact and lend without the need for access to a central server.

That’s extremely important in countries like Niger, where there’s less than 1% internet coverage and poor phone network coverage, but it will also be useful for places with better infrastructure, reducing network processing costs and the risk of centralised services. We hope to port the same technology into our Danish solution, helping small businesses here operate without the need to go through central authorities or banks, but maintaining incorruptible, fact-based reputations and financial records. We’re learning a lot from the customers we’re meeting in Niger, but the smallest businesses everywhere face the same problems.

The last thing the world needs is another bank. @wearehiveonline

You can read more about the challenges of the unbanked, microfinance, small businesses and how Fintech is helping to build financial inclusion in Fintech Revolution: Universal Inclusion in the New Financial Ecosystem (Sofie Blakstad and Rob Allen, Palgrave, 2018)